The first Friday of November is Familial Chylomicronaemia Syndrome (FCS) Awareness Day. This year we are delighted to be working in partnership with our UK-based network member, Action FCS, to raise awareness of FCS, and to amplify the under-estimated impact that living with the condition has on the lives of patients and those around them.

Familial chylomicronaemia syndrome, or FCS, is a rare familial hyperlipidaemia affecting between 1 in one hundred thousand people to 1 in one million people worldwide, with the lower prevalence of 1 in one million considered to be due to the lack of awareness and diagnosis.[1]

People with FCS have inherited faulty gene variants which affect the function of a protein called lipoprotein lipase (LPL) needed for breaking down dietary fat. In some people with FCS, the genetic variants affect LPL directly and in others the genetic variants affect the function of another protein required to make LPL work effectively.

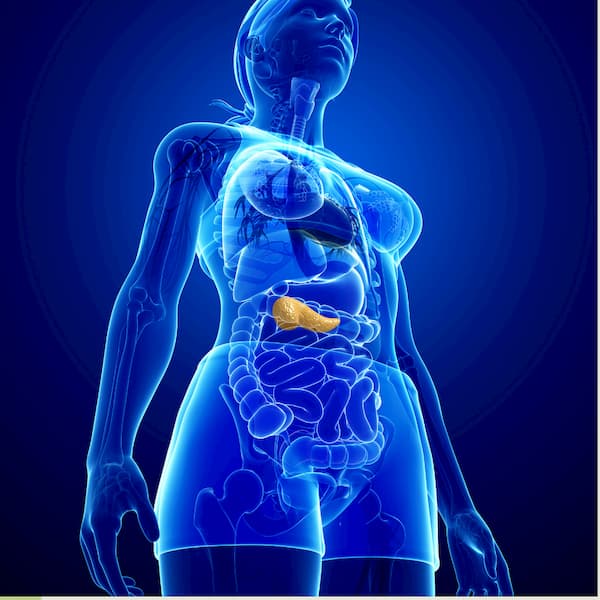

When fat is eaten in the diet it enters the bloodstream as triglycerides. Triglycerides are parcelled up with proteins into chylomicrons which are then broken down by LPL. People with FCS lack functioning LPL and cannot dispose of chylomicrons which remain in the blood and are responsible for its milky-white appearance. Chylomicrons circulate in the bloodstream and block small blood vessels in multiple organs which is thought to be how they cause the symptoms associated with FCS.

The most serious of the symptoms is pancreatitis which can be life-threatening. Pancreatitis occurs when the pancreas, a gland that lies in the upper half of the abdomen behind the stomach and in front of the spine, becomes inflamed. If someone has multiple attacks of pancreatitis it may become permanently damaged. If this happens it is no longer able to perform its main functions of secreting proteins (digestive enzymes) needed for digestion of food and producing hormones including insulin for regulating blood sugar levels. People with a permanently damaged pancreas from pancreatitis may develop diabetes and need to inject insulin and may also need to take digestive enzyme capsules with every meal.

Other symptoms of FCS include abdominal pain, which can be severe, hepatosplenomegaly (enlargement of the liver or spleen), xanthoma (reddish-yellow bumps or nodules), and ‘brain fog’ – poor memory and lack of concentration.[3]

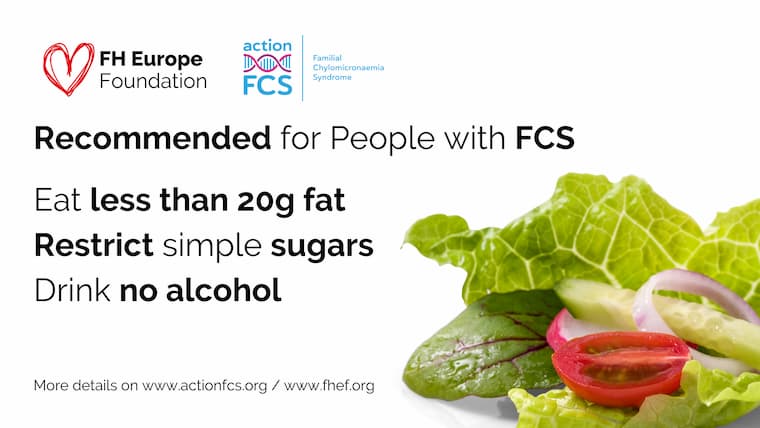

To reduce the risk of pancreatitis, patients are recommended to eat a diet of less than 20g of fat per day, avoid added sugars and drink no alcohol. The 20g fat limit includes both animal and vegetable fat, and fat found within food as well as added to food.[2] For many patients, 20g fat is too high and still leaves them at risk of pancreatitis and they may only be able to eat about 10g fat a day. They need to supplement their diet with a medically prescribed oil called MCT oil (medium chain triglycerides).

People with FCS are at an increased risk of developing diabetes either because they develop insulin resistance from having to substitute dietary fat with carbohydrates and sugary foods, or because of insulin insufficiency from recurrent bouts of pancreatitis, or a combination of both.

FCS is an autosomal recessive condition, meaning that to have FCS, a person must have two faulty copies of an FCS-causing gene. There are 5 known genes which cause the condition (LPL, LMF1, APO C-ll, APOA5, and GP1HB1).[3] Each of their parents have only one copy of a faulty gene and are usually unaffected by the condition themselves but are ‘carriers’ of the condition. When two carriers have children, each pregnancy has a 25% chance of producing a baby with FCS, a 25% chance of the baby having no faulty genes, or a 50% chance of the baby being themselves a carrier.

Patients can be diagnosed at very different times in their life. Some are diagnosed from birth or in early childhood, while others reach their forties before they achieve a diagnosis. Those diagnosed later in life have usually struggled with unexplained symptoms and can have gone through a long process of misdiagnosis, or of having had their symptoms trivialised, misattributed to alcohol abuse in the case of pancreatitis, or ignored. This process is well known throughout the rare disease community as the diagnostic odyssey.[4] Many of the patients diagnosed as adults have been hospitalised at least once with an episode of acute pancreatitis.[5]

Patients can have varying tolerance to fat, and manifest different symptom burdens, at different times of life. Whilst this appears to be related to the gene variant(s) causing their FCS, to date there has not been any comprehensive research to corroborate this opinion.

Keeping to the dietary restrictions places an enormous burden on people with FCS, who need to be constantly vigilant about what they are eating, and keep in mind what else they have eaten during the day to stay within their fat limit. How difficult this is for an individual can be affected by their cultural background and the role food plays in their society. For many people with FCS, there is very little awareness, education, and information available to support them.

‘Fat’ for people with FCS means all types of fat. Fat from oil, and from the foods from which the oils are derived – for example nuts, seeds, avocados, coconut, and olives. People with FCS can’t eat animal fats, so most meats unless great care is taken about how lean it is and any visible fat is removed. It can often be difficult to judge how much fat is in meat.

No fat from dairy (be aware that fat-free or low-fat products often contains high levels of added sugar), and no fat from egg yolks. For a more comprehensive view of the dietary restrictions you can find dietary guidelines here https://www.actionfcs.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Dietary-Guidance-for-FCS.pdf

Managing the dietary restrictions can have a financial burden – low fat foods can be more expensive to buy – but the impact of FCS can affect the individual’s ability to work and their subsequent income levels. Where people live can also have a great impact. Those in a major city with a wide range of shops close by have more opportunity to find ingredients that are suitable for them from different cuisines while people who live in in small towns or villages may have a more restricted choice.

Added to this mix, Is the level of understanding and support people with FCS get from the friends and family around them, the amount of information they have been given and understand about their condition, their access to a hospital or a doctor who has at least heard of FCS, let alone understands it, and the support they receive from professionals to help them manage the psychological aspect of living with this rare, and largely invisible condition.

Because of the burden of living with FCS, people with the condition are also more likely to struggle with mental well-being. This is partly because of the challenges of keeping to such a severely restricted diet as described above, which can make eating socially extremely difficult and lead to feelings of isolation. Also, they live with the constant worry of pancreatitis and may often feel unwell from physical symptoms associated with FCS and pancreatitis.

We’re calling on you to learn more about FCS and appreciate the challenges that people with FCS face in the attempt to manage their disease and asking you to Take the FCS 10g Fat Challenge You can read more about it on www.actionfcs.org and https://fhef.org/news/take-the-fcs-10g-fat-challenge/